G. Löwensohn – Children's Books – Fürth: A Story of Triumph and TragedyWritten by Jo Tisinger, Vintagepopupbooks.com Originally published as "G. Löwensohn – Children's Books – Fürth," by Jo Tisinger, in Movable Stationary, Volume 22, Number 1 (2014)Updated and edited here on 10/16/2024"Copyright © Vintagepopupbooks.com. All rights reserved. This content may be cited with proper attribution to Vintagepopupbooks.com and a link back to the original source.

This composition serves as an informational piece rather than a scholarly research document. Despite this, considerable effort has been dedicated to ensuring the content's accuracy and engagement. The material draws upon a wide spectrum of resources, with explicit citations included for direct quotations only. Should you require specific source details for any content, please reach out to us at [email protected].

For those of us interested in the historical details of movable books, we owe a great deal to the legacy of G. Löwensohn and his family. Theirs is a complex and memorable story of Triumph and Tragedy – a story that deserves to be told….

The G. Löwensohn company of Fürth was a prolific publisher, printer, and lithographer that operated in Bavaria during the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. German chromolithographers, mostly based in Bavaria, came to dominate the trade with their low-cost high-volume quality productions. Löwensohn was the largest and most prolific children's book publisher in Germany at the time.

The company was founded by Gerson Löwensohn (1817-1871) in 1844 on Schwabacher Str. in Fürth Bavaria, Germany.

He was relatively affluent, thanks in part to Isaac Löwensohn (1777–1854), Gerson's father, a prosperous merchant who became a shareholder during the establishment of Germany's first railroad, connecting Nürnberg and Fürth.

Gerson started out as a one-man copper plate printer producing picture sheets, coloring, and picture books. He added lithography in 1859. There is evidence, however, from earlier references, that he and his Father Isaac (1777 – 1884) were doing copper plate printings as early as 1838 - before Gerson received a license for a copperplate printing company in 1844 after he had completed an apprenticeship as a Kupfer- und Stahlstecher (copper and steel engraver) and had acquired the necessary license to operate his own business. He opened his first store on Schwabacher Str. (Star Road) in 1844 after he needed more space to produce his own work and began offering his own and others' products... Gerson had 5 brothers and sisters, none of whom were involved in owning the business.

Gerson Löwensohn opened his store at Sterngasse 175 on September 14, 1850, where he offered a range of products, including school atlases, steel engravings of personalities and city views, coat of arms and motto prints, letterheads, and forms of all kinds. Books came later, and movables even later. After specializing in the production of picture sheets, he incorporated a publishing business into the Lithographic Institute on October 1, 1856. According to the Publishers' Catalogues of the Publishers of the German Empire up to 1880 (archived at Columbia University, USA), he began printing picture books that he personally designed. The text for these books was also produced using lithography. In 1860, Löwensohn was offering 40 books for sale. An old invoice signed by Gerson in 1864 states the company name of G. Löwensohn's Buchhandlung Lithogr. Anstalt & Druckerei ( translates to:G. Löwensohn’s Bookshop, Lithographic Institute & Printshop) This name reflects the expansion and formalization of his business into both printing and publishing, serving a wide array of customers. According to an ad in Adressbuch der Stadt Fürth: nach amtlichen Unterlagen (1860), p. 176, G. Löwensohn in Fürth, lithographic institute and printing house, coloring and engraving company, publishing house,picture books, picture sheets, writing pads, decorated writing paper, family trees and sheets, visiting and greeting cards, drawing templates, gummed labels, envelopes, steel engravings, gold, devotional and household pictures, business signs, advertisements, bills, receipts, invoices, railway and shipping freight letters, etc. Also, all kinds of lettering, pictures, and label-related work, as well as the engraving of seals, stamps, and templates upon request, are carried out with care.

Löwensohn's adoption of lithographic color printing in 1869 was a pivotal moment in his publishing business. Prior to this, illustrations were typically hand-colored, a labor-intensive process that significantly limited the number of copies that could be produced. By embracing lithography, Löwensohn was able to mechanize the coloring process, which led to a dramatic increase in production capacity. With lithographic color printing, it became possible to print up to 400 prints per color per workday, a significant improvement over hand-coloring techniques. This innovation allowed Löwensohn to produce books with vibrant illustrations at a much faster pace, making his publications more widely available and affordable. The new technique also improved the consistency and quality of the printed images, as it allowed for more accurate and detailed reproduction of illustrations compared to hand-colored methods.

Gerson and his wife Helene (nee Zenner) (1821 – 1914) had two sons, Bernhard (1849-1910) and Theodore (1853 -1931), and one daughter Clementine (1847-1923). Although the boys helped out in the shop while growing up, Gerson did not bring his sons full-time into the business until each had graduated from high school. Gerson Löwensohn passed away on February 24, 1871, at the age of 53, as a result of a stroke (known in German as a "Hirnschlag"). His death was unexpected, and it marked a significant turning point for the company he had built in Fürth, Bavaria. Following his death, his wife Hélène, née Zenner (1821–1914), managed the business with their two sons,Bernhard (22 years old) and Theodor (18 years old) They took over the business and successfully continued its operations. The company also introduced new products, including more sophisticated children’s books, which featured intricate mechanical elements like pull-tabs and pop-up scenes.

Helene Löwensohn announced in the Fürther Tagesblatt that she would continue operating the family business with her 18-year-old son, Theodore. This statement likely served to reassure clients and partners that the business would remain stable and operational, despite any potential disruptions, signaling a smooth transition in leadership within the family. Helene ran the family business along with Theodore until Bernhard returned from a 5-year stay in the U.S.A. Helene’s great-granddaughter Anne Marie described her later as “A woman with strong morals”. The boys were smart, educated, and had learned a hard work ethic and strong morals from their parents. The sons benefited from the fortunate position of being able to draw upon the wealth accumulated by their grandfather, Isaac Löwensohn (1777-1854).

The sons were also quite generous. They contributed to the city of Fürth by donating to projects such as the municipal theater and the maternity hospital during celebrations like their children's weddings and other joyful events. As a tribute to their generosity, a street in Fürth-Westvorstadt today still bears the name Löwensohn Street.

In 1876 they moved from their smaller location in Sterngasse to a larger one at the Blumenstrabe. They were now fully running the company and bought a steam-powered Schnellpresse “Quick Press*,“ a lithographic press, to print by machine rather than by hand. They were very proud of the new machine and felt that it would allow them to expand. That they did. In 1882, the two brothers built a large factory on the Summer Road at 16-18/Ecke Birch Street. The new building equipped with the latest technological advancements, including electric lighting, which allowed for continuous expansion over time. With the exception of the paper and cardboard, the entire production process for the picture books was handled in-house. They expanded their production to include a wide variety of picture books, These publications were produced in multiple languages, such as German, French, English, Swedish, Danish, Dutch, Polish, Czech, Hungarian, Spanish and even Russian. Given the wide range of foreign-language books, Löwensohn naturally focused heavily on exports. It is unclear however, how many languages their movable books were translated to. Their credo, which could also be found on the company's letterhead, was picture books in all languages.

About Berhard: In 1880, Bernhard Löwensohn married Sophie Morgenstern (1862–1927). Together, they had two daughters: Frieda (1882–1957) and Emmy (1887–1941).

About Theodore: Theodore Löwensohn married Rosa Stockheim (1862-1934) in 1882, and the couple had three children: Gustav Löwensohn,(1883 -1943); Johanna Löwensohn, (1886 -1934); and Robert Löwensohn, (1895 -1945).

Note that In 1884, the Löwensohn factory began housing L. Kleefeld & Co., a game production company founded by Ludwig Kleefeld with support from the Löwensohn family. The two companies worked closely together, with the Löwensohn factory producing prints for board, card, and other games. In 1888, Kleefeld's half-brother Albert Rosenfelder (1864 –1916) games factory. Then in 1890, after contributing 100,000 gold marks, he became the third partner in the Löwensohn picture book factory. The company transitioned into a general partnership.

About Albert: On August 28, 1893, Albert Rosenfelder ( 1864- 1916) married Dora Heim (1872–1958) in Heidelberg. Albert and Dora had three children: Johanna Gertrud (1898–1995), Lisbeth Rosenfelder (1907–1907), and a son, Ernst Rosenfelder (1894- 1976). Albert 1916, the victim of an "accident" when he was leading maneuvers as

an officer.

They dramatically grew the business and added a bookstore to what became known as the Fürth Storybook Factory at Sommerstraße (Summer Street) 16-18. At its peak, hundreds of workers were employed there. By 1894 they were using the Quick Press to produce 3,000 prints per day. Before Quick Press, they could only print 400 per day – all by hand. Having joined the Industrial Revolution, the family’s social status, as well as their wealth, climbed. The letterhead of the company at that time showed the Factory building on “The Summer” with a smoking chimney, the proud symbol of the industrial age at the time. The logo’s slogan read "Picture Books in all languages." Also by 1894 Löwensohn was producing over 700 titles in 11 different languages. They published children’s books in German, French, French, English, Swedish, Danish, Dutch, Russian, Polish, Czech, Hungarian and Spanish. In 1894 Bernhard said that images from England were the most beautiful of all and they were spending thousands of guilders annually to purchase images from English printers. The company promoted the fact that they could deliver picture books in any language as long as the text was provided by the buyer. This helps to explain why books with the same movables sometimes have different text in different language editions. Löwensohn successfully found buyers among publishers in all these foreign countries. They also sold books in other countries without another publisher’s participation.

G. Löwensohn Letterhead – late nineteenth century (image from The Historical Society Fuerth)

Exports were critical to Löwensohn. Their massive growth was largely attributable to exporting. The Löwensohn family prospered. The family initially lived on the second floor of Blumenstrasse 15 above the factory premises of the picture book factory but soon the brothers built mirror-image mansions in the Hornschuchpromenade, the main avenue of the upper class in late 19th Century Fürth to show off their wealth and success. The Löwensohn mansions were designed in the neo-renaissance style, and they were adorned with ornate decorations and luxurious furnishings.

At its peak, Löwensohn employed hundreds of workers. The brothers and cousin Albert were well liked, respected, and they treated their workers very well. However, despite their generosity, the working conditions at Löwensohn were demanding. Workers often faced long shifts, typically between 12 and 14 hours a day, six days a week, with Sundays off. Additionally, the company had strict policies, including payroll deductions for tardiness or damages caused by workers. This practice was common during the Industrial Revolution, where long hours and strict discipline were often required to maintain productivity in factory settings.

According to an ad in 1893 - G. Löwensohn in Fürth (Bavaria) Lithographic Institute, Stone and Book Printing. Founded in 1854. The company primarily focuses on the production of picture books, on canvas, paper, and cardboard, in all languages, as well as youth literature and chromo albums on a large scale. Specialty: Die-cut picture books.A number of works are executed in the factory.

The Löwensohn family's remarkable generosity is reflected through their numerous charitable efforts. They established foundations to support causes such as infant care, tuberculosis treatment for children, and assistance for disabled veterans, widows, and orphans. Notable donations were made to local institutions, including the Maternity Hospital and the Municipal Theater in Fürth. In 1891, Theodor Löwensohn, on behalf of his wife Rosie, gifted the town of Cadolzburg with a Forest School for convalescent children, a project that continued to grow with further donations. The family also founded workers' foundations to provide financial aid to their employees and their families, ensuring support in times of need. Additionally, the Löwensohns contributed to numerous local clubs, associations, and initiatives aimed at improving community welfare. Their philanthropy was so impactful that a street in Fürth was named Löwensohnstraße in their honor, recognizing the lasting influence of their contributions.

Theodore Löwensohn, the primary force behind the growth of G. Löwensohn

Houses of the brothers Theodore and Bernard, Hornschuchpromenade 3 and 4 (image from The Historical Society Fürth)

Wages in Germany at the time were much lower than wages in the United States. We often talk about American publishers having their work done in Germany because the German print technology and lithographic quality was the best. That may have been true, but we suspect that lower cost was a primary incentive to “print in Bavaria.” In 1908, The Löwensohn lithographers, like other German company lithographers, were paid $5.50 - $8.25 per week, depending on ability. The average weekly pay for lithographers in the United States that same year was $25 per week – or about 340% higher. High quality and low cost, it’s no wonder that so much printing work came out of Germany.

After Bernhard passed away on September 19, 1910, his two daughters, Frieda Lessing, and Emmy (1887–1941), transferred their shares to their uncle, Theodor Löwensohn. In 1914, Theodor, along with Albert Rosenfelder, oversaw the construction of a new, modern factory at Maistraße 13.

Theodore and his wife Rosie (vee Stockheim) ( 1862-1934) had three children, Gustav Ernst (1883 – 1945), Johanna (1886 - 1934), and Robert (1895 – 1945).

When World War I broke out in August 1914, the factory faced significant challenges as many of its male workers were called to serve as soldiers. Theodor Löwensohn's son, Gustav, who had been part of the company's leadership since 1905, was also drafted into the military. During this time, the factory adjusted its operations to meet the demands of the war, producing books that appealed to all age groups, with a focus on themes that resonated with the patriotic sentiments of the era. It is interesting that Gustav was intellectual who knew foreign languages, was mobilized as an interpreter, and spent at least part

of the war in the rear, interpreting for the commander of a prisoner of war camp.

(see Gérard Langlois reference)

The publishing house continued to expand even in the difficult years after the end of the First World War. The Löwensohn Picture Book Factory and the L. Kleefeld & Co. Games Factory had a close business relationship, with the Löwensohn family supporting Kleefeld's establishment in 1884. Both companies initially operated from the same premises in Fürth. In 1927, the games factory L. Kleefeld & Co., which was also growing, moved with its up to 180 workers into the former Berlin department store at Nürnberger Strasse 129 / corner of Kurgartenstrasse. . This move freed up additional space for the picture book factory on Sommerstrasse. The new facility on Nürnberger Strasse also featured large salesrooms, which were shared with the Löwensohn picture book factory.

On July 1, 1916, during the war, Albert Rosenfelder passed away from a fatal headshot after falling from his horse during an infantry exercise at the Hainberg Troops Training Area. The murder has remained unsolved to this day. His stake in the Löwensohn picture book factory was inherited by his son, Ernst Rosenfelder, who was in the United States at the time and only assumed ownership upon returning in December 1919. In that same year, In July , likely in celebration of the company’s 75th anniversary, Theodor Löwensohn transferred his remaining share of the Löwensohn Picture Book Factory to his sons Gustav and Robert. Gustav, at 36, became the managing director, while the younger Robert age 24 and Ernst Rosenfelder age 25 —assisted him in running the company. After demobilization, Robert entered the family business in early 1919. Despite stepping back, Theodor continued to work as the senior manager until his death on April 10, 1931 at the age of 78.

About Gustav: Like his father and Uncle, Gustav (was an exceedingly kind man. He married a beautiful woman named Emmy (nee Mannheimer) (1885-1978), The couple had two daughters, Lilli (1908-1941) and Dora (1911-1976). Starting in 1912, the family resided in a newly constructed villa at Forsthausstrasse 43 in Dambach-Westvorstadt. Emmy carried on the Löwensohn wives' tradition of energetic volunteer and social work.

About Robert (1883 - 1945) : On June 14, 1919, Robert married Ella-Ruth Mündheim (1895-1942), the daughter of Swedish ophthalmologist Max Mündheim, in Würzburg. The couple had three children: Anne-Marie (1920-2015), Hans Felix (1922-1923), and Gerhard (1926-2013). Initially, they lived on the second floor of Königswarterstrasse 56, and in 1928, they moved to a villa at Bismarckstrasse 25 in the Dambach district of Fürth.

About Ernst:On December 29, 1920, Ernst Rosenfelder married Elisabeth Dormitzer (1899–1979) in Nuremberg. Elisabeth was the daughter of Sigmund Dormitzer, a Nuremberg lawyer (1869–1944), and Else Dormitzer, a writer (née Forchheimer, 1877–1958). The couple lived at Hornschuchpromenade 44 and had two children: Dora Rosenfelder (1922–2016) and Albert Georg Rosenfelder (1925), who later adopted the name George Rogers.

For the next 18 years, the company continued to grow under the leadership of Gustav (President), Robert, and Ernst. As the company prospered so did their families, their workers, and the community of Fürth.

After World War I, Germany's toy and children's book industries faced significant challenges. Restrictions on raw materials and a reduced workforce made production increasingly difficult. The political instability and social upheaval following the collapse of the previous regime further complicated the situation, worsened by the rampant inflation that plagued the country. Many nations, particularly the United States—whose economy had strengthened during the war—imposed high import tariffs to protect their emerging toy and publishing industries. For Germany, whose toy manufacturing sector heavily relied on exports, these trade barriers presented considerable obstacles throughout the 1920s. In response to fierce competition, German producers sought to expand both domestically and internationally. This led to a period of streamlining and consolidation within the industry. The Löwensohn family renamed their company Pestalozzi-Verlag around 1929, as a response to growing anti-Semitic pressures in Germany during the Nazi regime. The renaming was a strategic attempt to present a less overtly Jewish name. The family's company had already begun consolidating and seeking to expand its reach domestically and internationally due to fierce competition in the publishing industry during the 1920s. Gustav Löwensohn initially managed the newly renamed Pestalozzi-Verlag, but as the situation for Jewish business owners worsened under the Nazi regime, Emil Franke (1907-1984) took over management in 1933 when the company was restructured and renamed Pestalozzi-Verlag, Graphische Gesellschaft mit beschränkter Haftung. This was part of broader efforts to shield the company from overt Jewish associations. Despite this, the Löwensohn family was eventually forced to sell the business in 1937 to Kunstanstalten May AG in Dresden. Around the same time, in 1929, Robert Löwensohn and Ernst Rosenfelder founded a subsidiary company - BIAS Verlag GmbH - in Fürth along with a partner, the Montreuil printer Louis Vilette. BIAS stands for Bilderbücher In Allen Sprachen ("Picture Books in All Languages"). From 1933, its distribution took place outside conventional channels like kiosks and haberdasheries. Half of its production came from the Loewensohn publishing house's resources (which became Pestalozzi Verlag in 1935), while the other half was commissioned from prolific illustrators involved in the popular imagery sector, such as René Touret, A. Capendu, and Gordinne/Chagor editions in Belgium. While both Pestalozzi and BIAS Verlag were part of the publishing industry, BIAS Verlag focused primarily on publishing and distributing picture books in multiple languages. The name "BIAS" reflected their motto, "Picture books in all languages," with a clear orientation toward international exports. In contrast, Pestalozzi-Verlag focused more on domestic and educational publishing. Despite the successes achieved during this period, the prosperity of the Loewensohn Family would be short-lived............

Enter the Nazi Third Reich – The end of the Löwensohn Dynasty

The rise of the Nazi Third Reich marked the end of the Löwensohn dynasty and the devastating loss of their business, wealth, and community.

On April 1, 1933, a nationwide boycott targeting the Jewish population was initiated across Germany. The Fürther Anzeiger published a detailed list of "Jews and Jewish businesses in Fürth subject to the boycott," which included the Löwensohn Picture Book Factory and the L. Kleefeld & Co. Games Factory. By the end of 1935, Jewish publishers were prohibited from printing and selling books. According to his niece, Anne-Marie Vitkine (1920–2015), Gustav Löwensohn, who served as the chairman of the Association of German Picture Book Publishers and Manufacturers, traveled to Berlin by train to appeal to the Reich Minister. He argued that Jewish publishers contributed significantly to the global export market, bringing in much-needed foreign currency for the state. While this appeal temporarily delayed restrictions, the ban on Jewish publishers was ultimately enforced two years later. With the rise of the National Socialists in 1933, the Jewish-owned Löwensohn company faced significant hardships. On December 1, 1937, Gustav and Robert Löwensohn were compelled to sell the business to Kunstanstalten May (KAMAG) in Dresden receiving only 5% of the sale price - 571,290 Reichsmarks = while the Nazi regime seized the rest.

This sale occurred two years after Nazi Law prohibited Jews from being in the printing/publishing business in Germany. The forced sale of the G. Löwensohn company in 1937 was a tragic consequence of the Nazi regime's anti-Semitic policies. As you noted, the Nazi government prohibited Jews from owning or working in the printing and publishing industries in Germany, effectively forcing the Löwensohn family to sell their business. 95% of the money derived from the sale of the business went straight to the Nazi state. The centerpiece of the family’s generosity “the Forest School and Colony” was turned into a Nazi Training Camp. In 1937 Gustav fled with his family to The Netherlands and later to Belgium. Unfortunately, In 1943, Gustav was caught by the Nazis in a roundup in Brussels and sent to the worst of Hitler’s concentration camps - Auschwitz.- one of the most notorious concentration camps of the Holocaust. It is a tragic reminder of the brutal realities of life for Jews and other targeted groups under the Nazi regime. While there he was forced to use his foreign language skills to be an interpreter for the commander. He then lost his life there two years later. His brother Robert and wife Ella Ruth (vee Muendheim) (1895 – 1944) had escaped to France with their children but were deported back to Germany and then to KZ Auschwitz, Oświęcim County, Lesser Poland Voivodeship, Poland - where they also perished at the hands of the Nazis. Robert perished during a death march from the Blechhammer forced labor camp near what is now Mościsko,

The third partner, Ernst Rosenfeld, survived in exile. The Rosenfelder family had left Germany for the United Kingdom in the summer of 1938. Following the end of World War II in 1945, Ernst began rebuilding his career in publishing in London.

Gustav’s wife Emmy and one of their two daughters, Dora (1911 – 1976) survived the war and immigrated to the United States as soon as it was over. The second daughter Lilli (1908 – 1940) was killed in London during “The Blitz” air raids by the Germans which were a devastating series of bombings carried out by the German Luftwaffe during World War II. All of Gustav’s descendants are from daughter Dora and live in the United States*.

Robert and Ella Ruth’s children Anne -Marie (1920-1998) and Gerard (1926 - ?) were not deported back to Germany. They survived and spent the rest of their long lives in France. According to the autobiography of Anne-Marie, posted online in 2002 - Gerhard, as the only male heir, had been destined to take over the firm… had Hitler not intervened.

*Vintage Pop-Up Books has been in communication with Jane Chu, former chairman of the National Endowment for the Arts (2014-2018) and a friend of Herb Kohn. Herb is the grandson of Gustav Löwensohn, Gustav was one of the sons of Theodore and Rosie. At eight years old, Herb and his family—his parents Dora (Ne: Löwensohn 1911–1976) and Walter Kohn), sister Annette, and grandmother Emmy (Gustav’s wife)—escaped the Nazis, hiding in Belgium until the end of the war. Jane Chu has written a concise account of Herb’s story, which was published in Smithsonian Folklife Magazine on August 28, 2023. Herb's family experienced significant hardships during World War II. While Grandfather Gustav perished, the rest of Herb’s immediate family, including Grandma Emmy, managed to escape Nazi-occupied Holland, a journey that was perilous and reflective of the broader Jewish experience of persecution during that time. You can access it here: https://folklife.si.edu/magazine/jewish-family-escape-from-holland

Regarding Gutov's death at the Auschwitz II-Birkenau extermination camp - As stated in Ms Chu's article linked above "One day in Brussels, Herb’s grandfather boarded a bus which was stopped and searched by the Nazis. He had been carrying false, non-Jewish identification, but was taken to the local prison and later transported to Auschwitz. “We never saw him again.”

As of this writing October 16, 2024 - Herb is still living

Aftermath... In 1937, under the pressure of the Nazi regime's anti-Semitic laws, the Bilderbücherfabrik Löwensohn was forced to sell its assets to Kunstanstalten May AG (KAMAG), a prominent fine art prints and publishing company founded in Dresden in 1882 by Friedrich Adolf May. KAMAG specialized in high-quality illustrated materials, postcards, and fine art prints, and was sometimes informally referred to as the "May Art Institute." In 1938, the business was restructured into a GmbH (a limited liability company) and renamed Pestalozzi-Verlag Graphische Gesellschaft mbH. Emil Franke, who had been with the KAMAG company since 1923 and served as an authorized officer, assumed the role of managing director following this transition. This marked a significant rebranding of the company, which continued to publish children's books under the new name. Emil Franke was considered a supporter of the Löwensohn family primarily due to his role in facilitating the continuity of their legacy and business interests during and after the difficult period of Nazi persecution. After the forced sale of the Löwensohn Picture Book Factory to Kunstanstalten May AG (KAMAG) in 1937, Franke became instrumental in managing the restructured company, Pestalozzi-Verlag. He ensured the company maintained its focus on children's literature, preserving the spirit of the original Löwensohn enterprise. After World War II, Franke played a key role in the partial restitution of shares to the Löwensohn family. He helped ensure that their descendants retained a voice in the decision-making process at Pestalozzi-Verlag, despite the significant challenges of the era. After World War II in 1949, shares of the former Löwensohn picture book factory were partially returned to the original owners. The families of Gustav and Robert Löwensohn, along with Ernst Rosenfelder, received 50% of the company shares, while KAMAG retained 50%. The family transferred 10% to Emil Franke Emil Franke, who had consistently supported both families. The contract required that no decisions at Pestalozzi-Verlag could be made without the approval of the Löwensohn descendants. From his London office, Ernst Rosenfelder,, the sole surviving member of the original ownership, managed the distribution of children's books under the newly established Brimax Books Ltd, focusing on English-speaking markets. His son George Rogers joined the business around 1970, further continuing the family’s involvement.

Post-War Justice: In 1947, a group of individuals—Josef Ebner, August Hörhager, Alois Hochrainer, Hans Riedl, Karl Handl, Hans Bayer, and Hermann Moser—were sentenced for their involvement in deploying a gang that persecuted Jewish families during the Nazi regime, including the Löwensohns. These individuals were sentenced to prison terms ranging from 6 months to 2 years. While these sentences aimed to hold perpetrators accountable for their roles in anti-Semitic actions, the relatively light sentencing reflects the broader challenges of post-war justice, where the atrocities committed often outweighed the penalties enforced. These trials were part of efforts to address the crimes of the Nazi era, but the outcomes have often been criticized for being lenient given the severity of the offenses committed.

Pestalozzi-Verlag (PV) had been originally founded in 1920 in Nuremberg and became a significant player in children's publishing, expanding internationally with the founding of Bias Verlag GmbH in 1929. Bias Verlag, co-founded by Robert Löwensohn and Montreal printer Louis Vilette, focused on distributing books internationally. In 1941, Robert Loewensohn, anticipating difficulties, made Louis Vilette the majority partner of the company, renaming it to "Société nouvelle des éditions Bias." This strategic move helped the business survive after Loewensohn's arrest and deportation to Auschwitz in 1942. During this period of conflict, the company sustained itself by leveraging its existing resources, particularly picture books, which allowed for low-cost revisions and adaptations. During the 1950s and 60s, PV grew to become a leader in children’s books, but in 1972 the company moved its production from Fürth to Erlangen, marking the end of picture-book production in Fürth.

in the 1980s, a significant portion of Pestalozzi Verlag was sold to Dr. Engelhardt, who already owned a majority stake in the company. This transaction marked a turning point for the publishing house, as it transitioned into new ownership while retaining some involvement from the Löwensohn and Rosenfelder families. Dr. Engelhardt’s acquisition further consolidated control over the company, paving the way for its eventual sale in the late 1990s and early 2000s to a Danish publisher, which rebranded the company as Egmont-Pestalozzi and moved its operations to Munich.

Publications from Pestalozzi Verlag under its original management ceased in 1992, marking the end of an era for the company in its traditional form. Following this, the business underwent restructuring and ownership transitions, leading to its acquisition by a Danish publisher in the late 1990s and rebranding as Egmont-Pestalozzi. The focus shifted to different markets and production strategies after this point. PV continued its success into the late 20th century, becoming the market leader in picture books and merging with VEMAG Publishing and Media AG. However, in 1998, the company was acquired by Egmont, a major Danish media company and one of the largest children's book publishers in the world. Despite this, financial challenges persisted, and by 2017, Pestalozzi-Verlag had filed for insolvency. During the restructuring process, some former employees from Erlangen founded BoardBook GmbH, continuing the company’s printing operations in the region.

Löwensohnstrasse ( Löwensohn Road) is a street in the Dambach district of Fürth, located in the Westvorstadt residential area. It was named in 1950 to honor the Löwensohn family, who were early founders of the city. The street runs north from Hardenbergstrasse and connects to a side road of Lindenstrasse, with a footpath leading to SchwedenstrasseToday, the old Löwensohn Storybook Factory in Fürth remains on Löwensohn Road. It was converted into a 31-unit luxury apartment building in 2014. They promote themselves as “Summer Lofts Fürth - Living in the former picture book factory Löwensohn”. The 31-unit apartment complex is now a vibrant part of the neighborhood, presrrving the historical charm of the former Löwensohn factory while offering contemporary living spaces.

Overall, the story of the G. Löwensohn business and the Löwensohn family is a complex one, marked by both innovation and success as well as tragedy and loss. It serves as a reminder of the importance of recognizing the historical context in which businesses and industries operate, and of the need to remember and honor the legacy of those who have been impacted by discrimination and persecution.

Section 2:

Notes on identifying Löwensohn produced books

The "Golden Era" of movable book production:

The golden age was made possible by the superior printing technology of chromolithography from Germany. The late 19th to early 20th centuries represent the golden era of movable book production because of the technological advancements, cultural popularity, and craftsmanship that defined the period, combined with the later decline (after World War I) of such elaborate production. World War I ended the golden age of movable books in Germany. The war destroyed Germany's printing and toy manufacturing centers, making it difficult to gather the manpower needed to produce movable books. Additionally, paper production decreased and the demand for "frivolous" pastimes declined. It would be over 50 years before movable books would again be in demand and published in large numbers.

During the nineteenth and early 20th centuries, the creation of movable pieces in books was a highly skilled process that relied on a combination of paper engineering techniques such as die-cutting, folding, layering, and sliding mechanisms. These techniques enabled the interactive elements—flaps, levers, pull-tabs, and pop-ups—to come to life. The paper engineering was often incredibly intricate, requiring precise measurements to ensure that each component moved smoothly without tearing or jamming. The illustrations on these movable pieces were printed using chromolithography, a cutting-edge printing technique at the time. Chromolithography involved using multiple stones to apply different colors, one layer at a time, to create vibrant and detailed images. This method gave movable books their signature richness in color, adding to their visual appeal and making them particularly attractive to children. The chromolithographs were then transferred to paper sheets, which would be die-cut or perforated to create the separate moving components. This was a precise and time-consuming process, as each piece needed to be aligned with the artwork so that the interactive features would function properly. Once the printed sheets were prepared, the real craftsmanship began. The manual assembly of these books required meticulous care. Teams of workers, often women and children in local workshops, were tasked with assembling the books by hand. Each layer of the illustration had to be carefully cut, folded, and glued to achieve the desired three-dimensional effect. Layers of paper were stacked and glued at different heights, creating the illusion of depth when the book was opened. The process also involved folding paper to create tabs, hinges, and other mechanisms. This required workers to make precise creases to ensure the elements would pop up or move smoothly. Hand-gluing the delicate movable pieces added another layer of complexity—too much glue or misalignment could prevent the parts from functioning correctly, making the entire assembly process highly specialized. Due to the labor-intensive nature of this work, movable books were significantly more expensive to produce than standard printed books. Their limited production, combined with the fragility of the paper mechanisms (which were prone to wear and tear), means that few of these books have survived in good condition, making them highly collectible today. The fragility and intricate craftsmanship required to maintain the delicate mechanisms also contribute to their rarity, as many books have not withstood the test of time. Identification: When a Bavarian printed movable book has a number on its cover, it often indicates a German mass-market edition, and in many cases, this points to Löwensohn as the producer. According to Göte Klingberg, movable books sold internationally without the involvement of a foreign publisher were typically undated, which makes them particularly challenging to identify. Without a clear publication date, researchers cannot use the usual method of consulting publisher catalogs to determine when a book was produced. This practice was common with publishers like Löwensohn, where the lack of a publisher's imprint and date made it harder to trace the book’s origin and timeline.

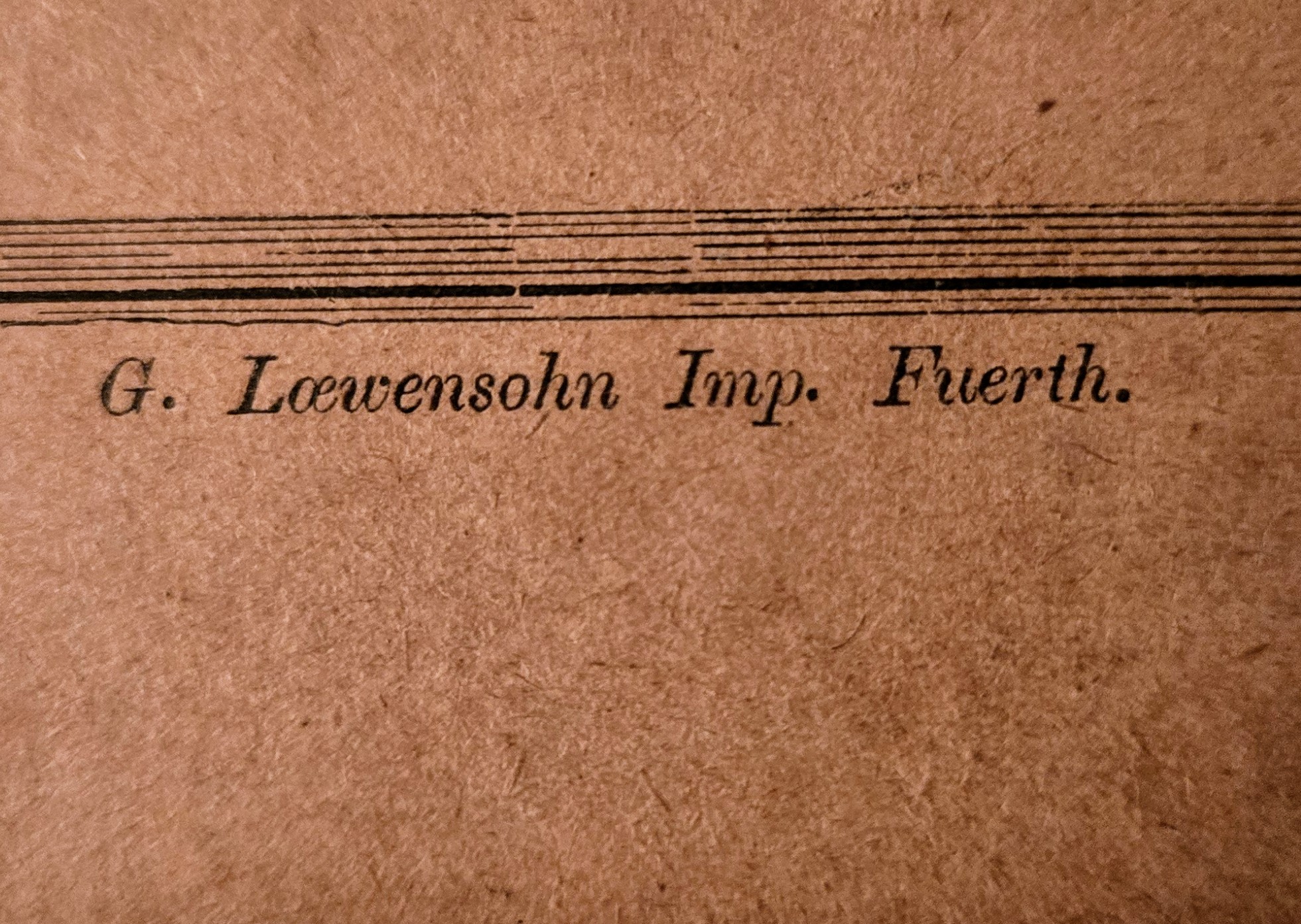

Löwensohn was the printer and sometimes publisher of many movables. Most of these books were printed for other publishers in various countries and usually did not bear a Löwensohn mark. “Printed in Bavaria” without a printer indicated often means it’s a Löwensohn. One reason that we know that Löwensohn was behind many of these movables is because French copies, for whatever reason, often had a small “G. Löwensohn Impr. Fuerth.” When no publisher mark or date appears on "printed in Bavaria" movables it is likely that Löwensohn marketed these books directly from Germany. The phrase “Printed in Bavaria” was not exclusive to Löwensohn, but it became a common identifier for their unbranded works. Note that Bavaria, particularly Nuremberg and Fürth, was a hub for high-quality printing and book production, making it an attractive location for many publishers. Other printers in Bavaria, such as J.F. Schreiber in Esslingen, Schaller & Kirn (Stuttgart and Bavaria), and Ernest Nister (Nuremberg) also produced movable books and interactive children’s literature during this time.

During and after World War 1 the prejudice of Americans toward Germany required Löwensohn to sell their books to that market without identifying that the books came from Germany. A great example is the “publishing front” Löwensohn set up in New York called The Pictorial Color Book Company. Through PCBC, they were able to successfully sell and distribute The Pictorial Moving Picture Books in America. In the U.S. and other countries, anti-German sentiment after the war prompted Löwensohn to operate through intermediaries like the Pictorial Color Book Company, allowing them to sell without openly revealing their German origins. There are also Moving Picture Books without any publisher information that were likely a first attempt to sell the books on Löwensohn‘s own before the war prior to 1914.

Brilliant Gustav could speak several languages. Learning to be multi-lingual undoubtedly arose from his family's expansive export business. We have records from the Ellis Island passenger archives that Gustav visited the United States in 1905 at the age of 22 and again in 1909 at the age of 26. Löwensohn’s multilingual abilities would have been a key asset in navigating international business, especially as the family’s publishing and printing firm in Bavaria specialized in producing high-quality movable books for export. His trips to America were likely aimed at fostering business relationships, scouting new markets, and understanding the tastes of American consumers. It was common for European entrepreneurs to travel to the U.S. during this time to capitalize on the expanding American market.

International Distribution and the Lack of Branding: One unique aspect of Löwensohn’s production is the anonymity of many of their works. Movable books produced by Löwensohn often lacked a clear branding or publishing mark, especially when they were sold internationally. For instance, many of their books carried only the imprint “Printed in Bavaria,” which made them harder to trace back to the Löwensohn factory. This practice was partly due to the need to navigate the political climate post-World War I, especially in markets like the United States where anti-German sentiment was strong. This is why books distributed by the Pictorial Color Book Company in the U.S. seldom carried explicit German or Löwensohn branding.

By omitting a clear publisher's mark, Löwensohn's books could appeal to a wide audience across various regions, as the anonymity gave local retailers more flexibility to market them under their own brands. This production method also allowed Löwensohn to serve different markets without being directly tied to one source or country, thus enhancing the books' global reach and adaptability.

Many counties had extreme prejudice against anything made in Germany once World War 1 started. According to a 1914 article, which appeared in the London Standard August 27, 1914, urging people not to buy cards and other printed matter “from our enemies” in evil Germany. Other interesting notes from the same article include that 90% of color printing sold in England was printed at the time in Germany and that paper cardboard and goods exported out of Germany in 1913 totaled over 13 million pounds.

France after 1900 was different: In France, legal requirements for publisher credits are shaped by the French Intellectual Property Code (CPI), which mandates proper attribution for works like books to protect intellectual property. However, credits for mass-market works, especially those exported, could vary, explaining Löwensohn's inconsistent imprint use across countries. Typically, French publishing agreements require the publisher’s name unless otherwise negotiated. The Syndicat national de l'édition (SNE) oversees publishing standards, but export strategies, particularly after World War I, allowed Löwensohn to avoid German branding in sensitive markets like the U.S. Löwensohn’s collaborations with French publishers like Capendu likely followed local norms, resulting in their imprint on some French editions

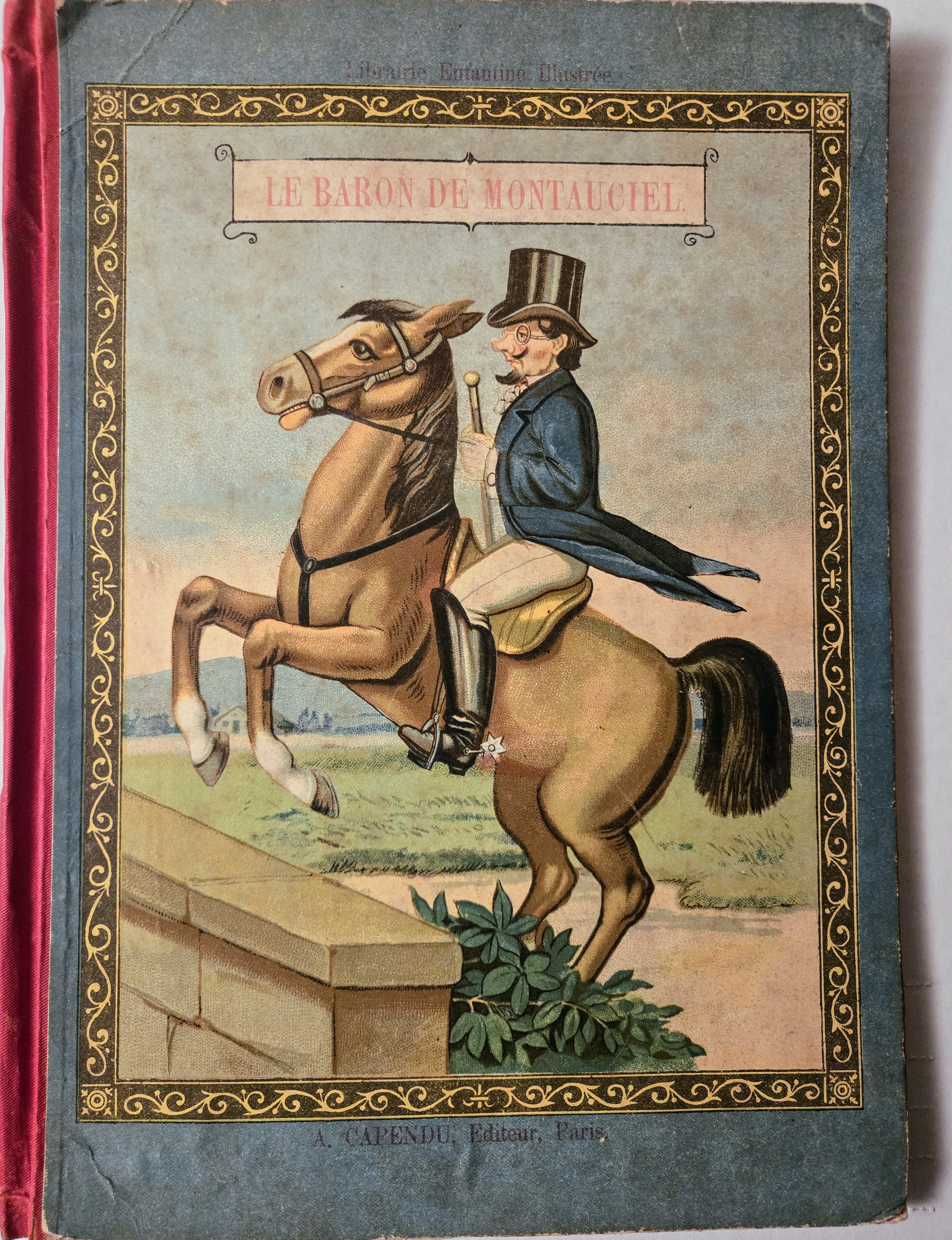

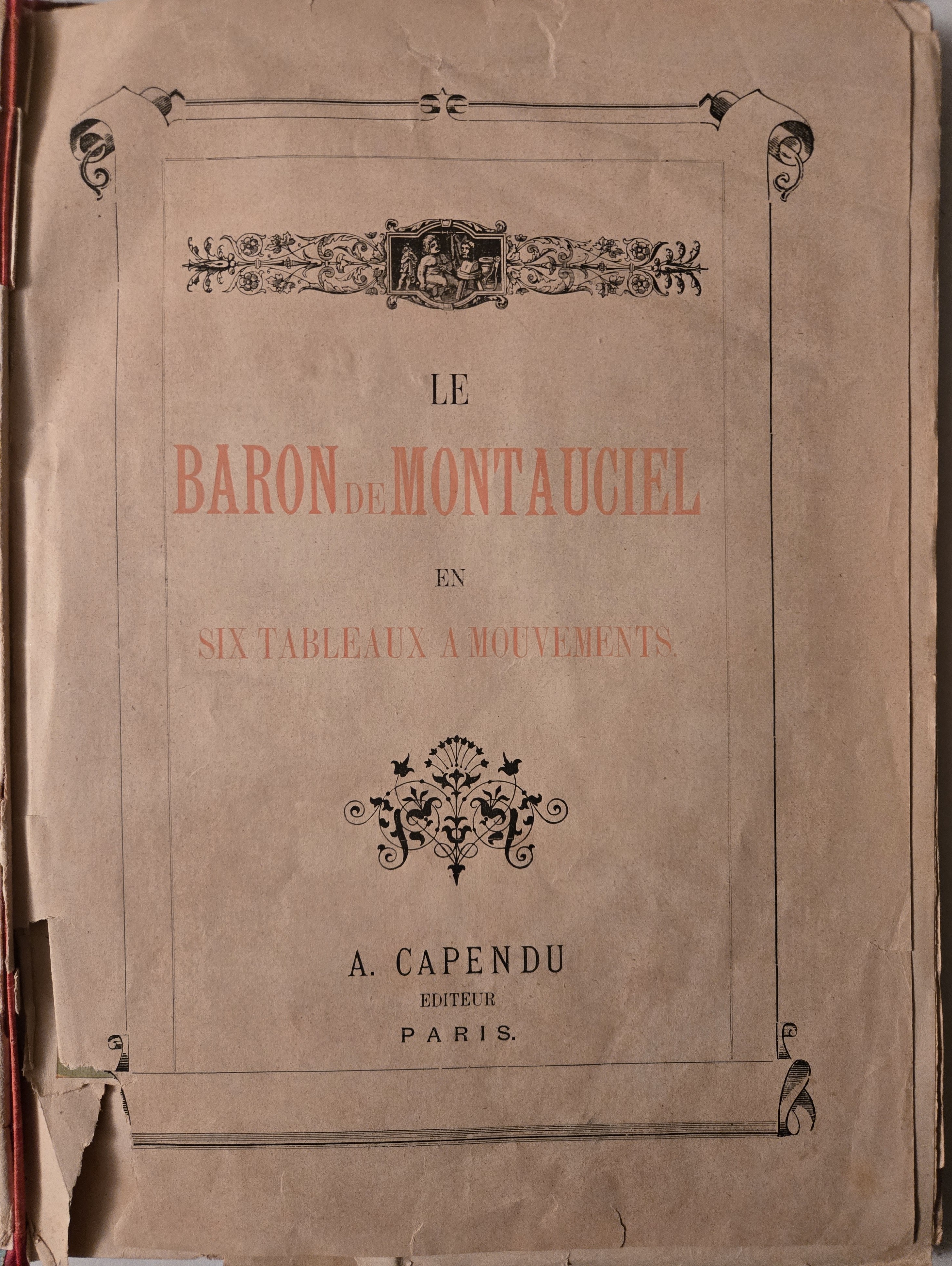

It is difficult to find non-French movables published before 1900 that have the Löwensohn imprint. An example of a French Movable with the Löwensohn imprint is an 1890 Capendu title, Le Baron de Montauciel with six movable pages. Another example of a Löwensohn Capendu movable is Grand Théâtre Féerique.

Capendu movable with Loewensohn imprint on verso - image from vintagepopupbooks.com

We have found the Löwensohn imprint on many Raphael Tuck movables and other movables as well. Frederick Warne has at least one, The Magic Lantern Struwwelpeter, printed by G. Löwensohn stating, "Designed in England and printed by G. Löwensohn at Fürth, Bavaria.

The oldest book reference we could find for a German movable book with a Loewensohn imprint was for Bewegliche Bilder für artige Kinder (Movable Book for Like Children) – 1866. We also Found a movable Lustiges Biderbuch ( Funny Picture Book) – 1871.

We have a couple of unusual Löwensohn English titles in our collection. One is an 1883 Löwensohn slot movable entitled "Fairy Tales For Children". The title page says “Transform Pictures” The tab pulls the slots to reveal a different image within the picture. G.M. Thurnauer was an importer and distributor based in New York during the late 19th century. His company, G.M. Thurnauer & Bro., was instrumental in bringing various European products, including movable books, to the American market. According to the August 2007 Movable Book Society Newsletter, another series published by Löwensohn was the Theatrical Picture Books published in several languages. They are relatively rare. Below are images from our copy of Too Much Talking is Hurtful (Little Red Riding Hood). It was published in 1883 along with 3 others, A Rare Cat (Puss in Boots), Awake ( Sleeping Beauty) and Poor Robinson ( Robinson Crusoe). Our English copy has what looks like a Löwensohn imprint, but it is too small and faded for us to read.  B Below are images for Löwensohn's Circ: 1880 grand first edition Theater Bilderbuch with all 4 scenes in one book: The 4 scenes are "Robinson Crusoe", "Puss in Boots", "Little Red Riding Hood" and "Sleeping Beauty" (Der arme Robinson , Der gestiefelte Kater , Rothkäppchen und Dornröschen) *Ries cites from Russell (1881, vol. 4, col. 542 and 1894, vol. 16, col. 5318) (Thank you Cherie, a collector from South Africa, for providing these images) We also have seen several copies of Löwensohn movables from the 20s and 30s in various languages that include books with vovelles as well as pop-up type books where a child can cut out pictures and stand them up. Some of these include The Traffic Light Book ( Vovelle, cut-outs) and The Home Farm and Around The World which include tabbed cut-outs that you can stand up to make scenes, and La Ronde Des Saisons Almanach des tout petits a( book with a turning vovelle cover showing scenes for each month – circa 1920) (shown below).  More Notes: *About the “Quick Press” – The Löwensohn brothers added their quick press in 1876. It was likely a Walter rotary press - developed in 1868 and run with gas. They were not the first German printer to do so, however. In 1832, Schreiber bought its first letterpress printing machine and in 1864, Ferdinand Schreiber, the older of J.F. Schreiber's two sons, imported the first high-speed lithographic press in Germany from France. Schreiber is best known as Meggendorfer’s publisher. The term quick press was originally used for one type of machine, and eventually all types of flatbed press. We know from an old ad testimonial written by Löwensohn that the company that manufactured at least one of their quick presses was "Steinmesse & Stollberg" and the model was “The Noris”. In the ad, they stated “I hereby like that the machine delivered to me, The " Noris," works to my complete satisfaction and gives rise to no complaints. Fürth i / B, 9 März, 1901. G. Löwensohn. In his 1894 speech marking the company's 50th anniversary, Bernhard Löwensohn outlined the significant steps taken to expand the business, reflecting on the strategic decisions that helped the company grow and thrive over the decades:

" In 1876 we moved our business to Blumenstrasse, into a house with large rooms, in which we also set up our first high-speed press, which was powered by a gas engine. Now the production took on a different appearance: the craft business became a factory, and instead of a daily output of 400 prints on the hand press, we could produce 3,000 on the high-speed press. At the same time we set up a bookbinding shop and shortly afterwards a book printing shop in our house, so that with the exception of the paper and cardboard, the entire production of the picture books took place in our house. Every single manual task, which previously required a lot of time, was now carried out as far as possible by ingeniously designed machines." If you would like to find out a lot of details about this press see Google book Allgemeiner Anzeiger für Buchbindereien, Volumes 17-18, pages 473-477. You can also email us at [email protected] for the link. Below is a drawing of an actual press Löwensohn owned in 1903:  Other - Below is a Löwensohn puzzle from 1900: Artists - We are still working on a list of artists that worked for Löwensohn - specifically with their movable books. We will update the list on our website as we find them. Paul Otto Engelhard: A prominent German illustrator, Paul Otto Engelhard contributed to several of Löwensohn's publications. He is especially noted for his work on the movable book titled "Kinderfreuden" ("Children's Joys"). Engelhard's career spanned various children’s books, postcards, and illustrations, including works for other publishers like Meggendorfer Blätter and the magazine Jugend. Heinrich Leutemann: Known as a popular animal painter and illustrator, Heinrich Leutemann collaborated with Löwensohn on various books. He illustrated titles like "Der Fuchs" ("The Fox") and "Die Schlittenfahrt" ("The Sleigh Ride"). Leutemann was particularly famous for his detailed depictions of animals, and he also contributed illustrations for works like "Bilder aus dem Völkerleben," published by Löwensohn, which showcased ethnographic scenes. Emil Weiss: Another key figure, Emil Weiss, illustrated several of Löwensohn’s movable books, such as "Tiere und ihre Jungen" ("Animals and Their Young"), published in the early 20th century. Weiss was known for his contributions to children's literature and movable book designs, blending vibrant artwork with interactive elements. ReferencesAdolf Berger sponge. (1968). Fuerth A to Z: A Historical Encyclopedia. Published by the city of Fürth, this work provides a detailed historical account of Fürth, including entries related to the Löwensohn family and their contributions to local industry. American Electrician, Weaver, W. D., Woodbridge, J. E., & Poole, C. P. (Eds.). (n.d.). Volume 10. This resource includes press photos and historical insights relevant to the publishing industry's technical advancements. Arrest of Nazis: Documentation Centre of Austrian Resistance. (n.d.). Postwar justice (Nachkriegsjustiz). Retrieved October 11, 2024, from https://www.novemberpogrom1938.at/en/taeterkreis/nachkriegsjustiz/

This site documents Nazi arrests and postwar justice, providing context for the political climate that affected businesses like Löwensohn. Chu, J. (2023, August 28). A Jewish family’s narrow escape from Holland: One child’s account of resistance and survival. Smithsonian Folklife. Retrieved from https://folklife.si.edu/magazine/jewish-family-escape-from-holland

Jane Chu highlights immigrant contributions to the United States, including Jewish cultural impacts. Fiorda 14-18. (n.d.). Robert Loewensohn. Retrieved October 11, 2024, from https://fiorda1418.wordpress.com/robert-loewensohn/

This article provides a historical overview of Robert Löwensohn and the family's influence on publishing. FürthWiki. (n.d.). Bilderbücherfabrik Löwensohn. Retrieved January 15, 2025, from http://fuerthwiki.de/wiki/index.php/Bilderbücherfabrik_Löwensohn

An in-depth entry on the Löwensohn Picture Book Factory, detailing its history and contributions to movable book publishing. Göte Klingberg - Svenska barnboksinstitutet. (n.d.). Pictures for children’s books on the 19th-century international market. This seminal work highlights Gustav Löwensohn's role in international movable book publishing. Holocaust Museum, Washington DC, United States. (n.d.). List of Holocaust Victims from Fürth. This collection lists victims, including members of the Löwensohn family, documenting their experiences during World War II. IMEC Archives. (n.d.). Parmi les archives des Éditions Bias. Retrieved October 11, 2024, from https://imec-archives.com/archives/carnet-de-bord/parmi-les-archives-des-editions-bias

Archives containing historical material on publishing networks, including links to Löwensohn. Jeuck, V. (Ed.). (1994). 150 years of Pestalozzi-Verlag. Erlangen: Pestalozzi-Verlag. This publication commemorates the history of Pestalozzi-Verlag, detailing its origins in the Löwensohn Picture Book Factory. Jewish Museum of Franconia. (n.d.). 89 King Street, 90762 Fürth.

The museum houses artifacts and documents related to Jewish families, including the Löwensohns. Kaznelson, S. (1962). Jews in German culture: Collective works. This book examines Jewish contributions to German culture, with mentions of prominent families like the Löwensohns. Meine Sammlung - Alte Kinder- und Jugendliteratur. (n.d.). Past Children's Books: Löwensohn / Pestalozzi Verlag.

A collector’s archive focused on historical children’s literature published by Löwensohn and Pestalozzi-Verlag. Peter Haining. (n.d.). Movable Books. London: New English Library.

Haining discusses the significance of the Löwensohn firm in producing movable books such as 'Ziehbilderbuch' and 'Ziehharmonika.' Picturing Childhood. (n.d.). Illustrated Children's Books from University of California Collections, 1550–1990. This collection showcases examples of early movable books and international publishers, including Löwensohn. Note: This curated collection highlights the evolution of illustrated children's books from the 16th century to the late 20th century, emphasizing the artistry and cultural significance of movable books. It includes examples of early movable book techniques, such as pull-tabs, pop-ups, and volvelles, showcasing their innovation and appeal to young readers. The collection also explores the contributions of key international publishers, including Gustav Löwensohn, who played a pivotal role in popularizing movable books in the 19th century. Second.wiki. (n.d.). Pestalozzi-Verlag. Retrieved January 15, 2025, from https://second.wiki/wiki/pestalozzi-verlag

A summary of Pestalozzi-Verlag's history, with ties to the Löwensohn Picture Book Factory. Tariff hearings before the Committee. (1909). Sixtieth Congress 1908–1909, Committee on Ways and Means Congressional edition. United States Congress.

This document includes discussions on wages and working conditions in industries relevant to Löwensohn's operations.

FürthWiki. (n.d.). Bilderbücherfabrik Löwensohn. Retrieved January 15, 2025, from https://www.fuerthwiki.de/wiki/index.php/Bilderb%C3%BCcherfabrik_L%C3%B6wensohn This article provides a detailed history of the Löwensohn Picture Book Factory, including its establishment, contributions to movable book publishing, and its challenges during the Nazi era. Duckipedia. (n.d.). Pestalozzi-Verlag. Retrieved January 15, 2025, from https://www.duckipedia.de/Pestalozzi-Verlag

An entry summarizing the history of Pestalozzi-Verlag, which emerged from the restructuring of the Löwensohn Picture Book Factory. It covers the company’s evolution and role in children’s literature publishing. Second.wiki. (n.d.). Pestalozzi-Verlag. Retrieved January 15, 2025, from https://second.wiki/wiki/pestalozzi-verlag

This source highlights the transition of the Löwensohn Picture Book Factory to Pestalozzi-Verlag, focusing on its operations post-World War II and its impact on the publishing industry. PosterPlakat. (n.d.). Kunstanstalten May AG (KAMAG). Retrieved January 15, 2025, from https://www.posterplakat.com/the-collection/publishers/may-fine-art-prints-publishing-dresden

This entry details the history of Kunstanstalten May AG, also known as KAMAG, a fine art prints and publishing company that acquired the Löwensohn Picture Book Factory under Nazi pressures in 1937. It provides insights into KAMAG's publishing legacy.

Fiorda1418. (n.d.). Bilderbücherfabrik Löwensohn. Retrieved January 15, 2025, from https://fiorda1418.wordpress.com/bilderbuecherfabrik-loewensohn/

Dormitzer, E. (2021). Traces of Memory: The Life and Work of Else Dormitzer (1877–1958). (The Holocaust: History and Literature, Ethics and Philosophy). Syracuse, NY: Syracuse University Press. Langlois, G. (n.d.). Histoire de la famille Löwensohn. Retrieved from https://fiorda1418.wordpress.com/bilderbuecherfabrik-loewensohn/ |