Martin Engelbrecht (1684–1756):

Martin Engelbrecht was a distinguished engraver, printer, and publisher who played a pivotal role in the intersection of printmaking and early visual entertainment.

History of Martin and his company:

Martin Engelbrecht was born in Augsburg, Germany. Engelbrecht was born into a family with connections to both the art and trade industries. His father, Johann Engelbrecht, was a paint dealer, and his mother, Anna Veronika Raminger, came from a family with ties to local commerce. Martin had a brother, Christian Engelbrecht, who was also an engraver and played a role in Martin’s early career development. Martin married twice. His first marriage in 1718 was to Sibille Wickert, the daughter of Andr. Wickert, a goldsmith in Augsburg. Together, they had one son and five daughters. Notably, his daughter Joh. Maria Christiana married Christian Wilhelm, an engraver and art publisher who later became an integral part of the family’s publishing legacy. Another daughter, Regina Barbara, married Gg. Christoph Neuhofer, a cotton manufacturer. After Sibille’s death in 1747, Martin married Margaretha Kern in 1749.

His early artistic development was influenced by his older brother, Christian Engelbrecht, who was ten years his senior and an established engraver. Martin learned the art of copper engraving from Gabriel Eigner, and after completing his training, he traveled to Berlin to work alongside Christian. Around 1708, he worked in Berlin with his brother, engraving prints after designs by Eosander.

In the early stages of his career, Engelbrecht and his brother moved to Vienna, where Martin’s skills were further refined while working on imperial ceremonies. This exposure to high-profile commissions at the imperial court helped him develop his talent for producing detailed engravings. During this time, Engelbrecht became a celebrated engraver, known for his portraits of monarchs and intricate landscapes, which dominated the print trade in Augsburg. These early works earned him widespread recognition and laid the foundation for his later innovations. The grandeur and precision required for his earlier engravings—especially those depicting rulers and expansive scenes—had a lasting influence on his artistry, particularly in the creation of his famed perspective theaters which he started around 1730.

In 1711, Engelbrecht returned to Augsburg, and around 1719, he founded his own print publishing house in partnership with Christian. That same year, he achieved a significant milestone when he was granted his first imperial privilege by Emperor Charles VI. This privilege was an extraordinary recognition of the value and originality of Engelbrecht’s creations. It protected his works from unauthorized reproduction, which was a common threat for printmakers at the time. The privilege, renewed in 1729 and 1739, emphasized Engelbrecht’s commitment to producing inventive and pleasing pictures that required significant time and effort to create. The imperial privilege stated that Engelbrecht was “greatly concerned that printed and colored engravings, based on his invention, might be imitated.” This allowed him to hold a monopoly on the production of perspective theaters.

The imperial privilege was a crucial factor in Engelbrecht’s success and prominence in the printmaking world. It gave him exclusive rights to produce and distribute his engravings, safeguarding his unique designs from imitation and piracy, which were common threats in the art trade of the time. This legal protection enabled Engelbrecht to innovate without fear of competition, allowing him to produce some of his most iconic works, including his miniature theaters and perspective dioramas. The renewal of the privilege underscored the recognition of Engelbrecht’s contributions by the imperial court, marking him as a trusted and respected artist. Few printmakers of his time enjoyed such privileges, which further distinguished Engelbrecht and solidified his influence across Europe.

Although this imperial protection greatly benefited Engelbrecht throughout much of his career, the privilege eventually expired after his death in 1756. By the late 18th century, as the cost of renewing the privilege became too high, unauthorized reproductions of Engelbrecht’s works started to appear. This led to increased piracy of his engravings, including his miniature theaters, which affected the business his family inherited. His son-in-law, Paul Martin Wilhelm, made efforts to secure new protection, but widespread reproduction by imitators posed a significant challenge, marking the end of the exclusive control Engelbrecht once held over his creations.

This imperial backing not only safeguarded his works but also enhanced Engelbrecht’s prestige. Few artists of his time were granted such privileges, marking him as one of the most respected and influential printmakers in Europe. The protection allowed Engelbrecht to maintain exclusive rights to produce and distribute his illuminated engravings, ensuring that his innovative techniques and artistic vision were recognized and preserved without the threat of imitation.

About Christian:

Martin Engelbrecht took over the art publishing house in 1735 after the death of his elder brother, Christian Engelbrecht (1672–1735). Christian was a notable German engraver and print-seller from Augsburg, Germany, and the older brother of the more famous Martin Engelbrecht. Christian and Martin collaborated closely, with Christian working as both an engraver and a publisher. Christian produced religious scenes, allegories, and prints depicting trades, which often complemented Martin’s optical works. While Martin Engelbrecht is often highlighted for his artistic achievements, Christian’s work as an engraver and print-seller significantly supported the family’s success in the Augsburg printmaking industry. Christian Engelbrecht’s contributions are often mentioned alongside his brother’s work, though Martin's optical theaters have drawn more historical attention. Nonetheless, Christian helped lay the foundation for the Engelbrecht publishing house’s artistic and commercial success in Augsburg.

Martin Engelbrecht’s Leadership and Business Expansion:

In 1718, Martin Engelbrecht married Sibylla Wickert, the daughter of a goldsmith and niece of Johann Stridbeck, a prominent engraver in Augsburg. This marriage further strengthened Engelbrecht's ties within the city's artistic community. After the death of his brother Christian in 1735, Engelbrecht took full control of the printing business. Under his leadership, the publishing house grew significantly and became one of the leading enterprises in Europe.

In a biographical account written by his son-in-law, Andreas Kilian, in 1742, Engelbrecht was described as a kind and honest businessman, well-regarded by his workers for his fair and respectful leadership. His business was located in Augsburg (near the Kappenzipfel, a district near a Capuchin monastery), at residence Litera C No. 90. The premises included a workshop, a bookshop, and an art dealership.

Martin was well-regarded by his workers for his fair and respectful leadership. His business was located in Augsburg (near the Kappenzipfel, a district near a Capuchin monastery), at residence Litera C No. 90. The premises included a workshop, a bookshop, and an art dealership.

By April 30, 1733, Engelbrecht's publishing house was fully operational, quickly gaining a reputation for its high-quality works. The business thrived due to Engelbrecht’s collaborations with numerous talented engravers and artists. According to contemporary sources, Engelbrecht was described as "a friendly, lively, and clever man, pleasant in his interactions, generous in his dealings, and esteemed among his fellow artists."

Friedrich Schott notes that Martin Engelbrecht collaborated with a significant number of skilled artists and workshop engravers. However, it remains unclear how much of the engraving work was done by Engelbrecht himself versus how much was based on his designs or transferred onto plates by others. The diversity in style and figures within the Theater collection suggests the involvement of multiple draftsmen. Among them might have been Christian Wilhelm, an engraver who married Engelbrecht's daughter around the time the collection was created, and Johann Wolfgang Baumgartner, an artist and draftsman known to have had a personal connection with Engelbrecht.

Engelbrecht oversaw a range of specialized graphic projects and collaborated with two key artists, Jeremias Wachsmuth (1711–1771) and Johann David Nessenthaler (1717–1766), to create designs for his renowned peepshows. Wachsmuth's contributions to these works are documented as early as 1731, while Nessenthaler's designs began appearing around 1737.

The Straßen- und Hofseite des Anwesens C 90 am Kapunziesel refers to the street and courtyard view of the property at C 90 in Kapunziesel, where the Engelbrecht publishing house and workshop were located..jpg)

Martin Engelbrecht’s work:

Martin Engelbrecht’s perspective theaters (also known as peepshows or optical theaters) are highly valued by collectors due to their historical significance, intricate craftsmanship, and rarity. As unique pieces of early 18th-century optical entertainment, these works have garnered increasing interest from collectors of movable books, antique prints, optical toys, and Baroque art. Engelbrecht’s works also hold cultural significance as a reflection of the Baroque fascination with illusion, theater, and scientific discovery. Collectors with an interest in 18th-century European culture and the Baroque period are often drawn to his works as representative of this era.

Engelbrecht’s works were often distributed through networks of print dealers and art shops across Europe. These dealers operated in major cultural and commercial hubs, and their networks allowed for Engelbrecht’s perspective theaters to reach a wide audience.

Martin Engelbrecht’s work as an engraver and publisher was prolific and diverse, encompassing numerous views of cities, portraits, and religious scenes. However, he is best known for his development of perspective theaters, also known as optical theaters or peepshows. By around 1740, Engelbrecht had perfected the complex layering techniques that allowed his dioramas to create a convincing illusion of depth and perspective. These were intricate paper constructions designed to create the illusion of a three-dimensional scene when viewed through an optical device, such as a magnifying lens or a mirror. Typically composed of 6 to 8 hand-colored, die-cut prints, these sets formed miniature theatrical stages that captured the imagination of 18th-century audiences.

These perspective theaters were often placed inside optical boxes, which enhanced the viewer’s experience by creating a more immersive and dramatic depth of field. This technique was similar to the elaborate stage sets of contemporary Baroque theaters, which aimed to evoke grandeur and scale. Engelbrecht’s ability to create such immersive experiences made his work highly popular and sought after during his lifetime. His peepshows were not just used for entertainment; they were also employed in educational contexts, where aristocratic families used them as tools for learning about history, religion, and society. Despite their delicate nature, many of Engelbrecht's dioramas have survived and are housed in museum collections around the world. These works include grand depictions of houses, gardens, Biblical scenes, and even scenes from everyday life, such as various trades.

Cut-out Figures: In addition to his renowned perspective dioramas, Martin Engelbrecht was deeply involved in the production of cut-out figures ("fogli da ritagliare"), which were meticulously designed sheets used to create layered scenes. These cut-out figures often depicted religious stories, scenes of daily life, or military settings, and they were another popular form of visual entertainment in the 18th century. These figures were sometimes used in dioramas or could be collected and assembled by buyers, further extending the interactive and educational nature of Engelbrecht’s work.

Engelbrecht's perspective dioramas were more than just visual curiosities; they were early experiments in creating optical illusions that would later influence the development of photography and cinematography. His work remains a significant milestone in the history of visual art, celebrated for its technical innovation and its role in shaping the future of entertainment. Through his mastery of copperplate engraving and the use of hand-colored prints, Engelbrecht created works that were both artistic and functional, providing viewers with new ways of perceiving and interacting with visual media.

Terminology and Classification:

There has been some confusion over what these types of prints should be called. The term "diorama" came into common use only later, in 1822, and earlier names for these works include Dioramen, Kulissen Bilder, or Guckkasten Theater. Today, Engelbrecht's work is usually described as Kulissentheater, Guckkastentheater, or Perspektivtheater in Germany; Diorami Teatrali in Italy; and "Petits Théâtres" or "Théâtre d'optique" in France. In England, they are referred to as peep shows. Engelbrecht’s original titles for these works, often found on the stage portal sheets in smaller formats, indicated their intended use for perspective views. The phrase used was “To be used for different portals to perspective views.” The word "perspective", derived from the Latin "perspicere," meaning “to see through,” is key to understanding the immersive visual effect Engelbrecht aimed to create.

Production and Form:

Engelbrecht’s peepshows were produced using thin copper plates and were colored with watercolors. The sheets came in three main formats: small, medium, and large.

- 180 x 220 mm: The largest format, often used for more detailed and intricate scenes.

- 90 x 140 mm: A medium format, typically used for slightly simpler but still visually engaging scenes.

- 73 x 90 mm: The smallest and rarest format, used for more intimate settings with less intricate detail.

These sheets were carefully numbered to denote their series or sequence, and this numbering system helped collectors and viewers understand the correct arrangement of the prints. Larger dioramas, often found in aristocratic settings, were preserved more frequently due to their high quality and popularity. The smaller versions, although designed with the same layout, had reduced detail due to the limitations of size, and fewer examples of these smaller dioramas have survived.

Collaborations and Innovations:

Engelbrecht’s collaborations with Jeremias Wachsmuht and Johann David Nessenthaler significantly expanded the reach and innovation of his perspective theaters. Each artist brought distinct skills that contributed to the refinement and complexity of Engelbrecht's dioramas, allowing his works to stand out in the competitive world of 18th-century printmaking.

Jeremias Wachsmuht, known for his precise and highly detailed engravings, played a pivotal role in producing Engelbrecht’s most intricate dioramas. Wachsmuht’s expertise in fine engraving techniques allowed for more elaborate designs that enhanced the illusion of depth in Engelbrecht’s peepshows. His ability to execute complex scenes, particularly those involving courtly life, religious allegories, and architectural views, gave Engelbrecht's perspective theaters a sense of realism and visual appeal that captivated audiences across Europe. Wachsmuht’s meticulous attention to detail also ensured that the layers in the dioramas aligned perfectly, making the optical effects even more striking. His contributions to the hand-colored engravings—a hallmark of Engelbrecht’s works—elevated the aesthetic quality of the dioramas, making them more visually engaging and collectible.

Johann David Nessenthaler, another highly skilled engraver, brought a distinct style that focused on clarity and precision in depicting depth and perspective. Nessenthaler’s engraving techniques, combined with Engelbrecht’s innovative use of layered prints, pushed the boundaries of what was possible with optical entertainment in the 18th century. His ability to render fine details allowed for more visually complex and immersive dioramas, which appealed to both aristocratic and educational audiences. Nessenthaler’s contributions to the perspective theaters introduced a greater sense of realism and narrative depth, further enhancing their popularity. His work enabled Engelbrecht to produce more elaborate scenes, often featuring dramatic action or detailed settings that created a heightened illusion of three-dimensionality.

Through these collaborations, Engelbrecht’s dioramas became more than just simple visual curiosities—they were masterpieces of optical illusion and storytelling. The precision and craftsmanship provided by Wachsmuht and Nessenthaler allowed Engelbrecht to push the art form further, creating works that were not only entertaining but also artistically and technically advanced for their time. This combination of innovation and technical excellence contributed to the widespread distribution of Engelbrecht’s works throughout major cultural centers such as Paris, Vienna, London, and Rome, solidifying his influence in the development of early optical art and scientific devices.

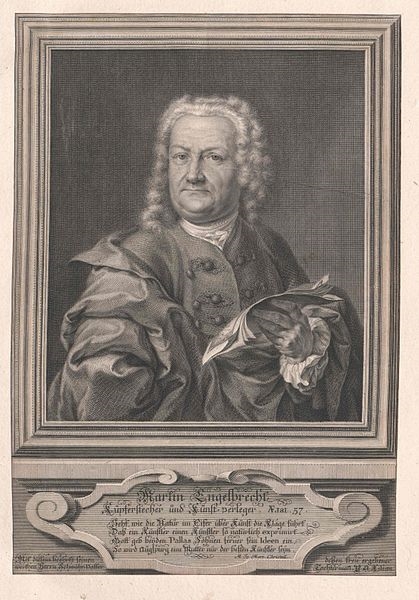

Portrait and Physical Description of Martin Engelbrecht: A Glimpse of the Man Behind the Art

A portrait of Martin Engelbrecht at age 57, created by Philipp Andreas Kilian, provides a rare visual representation of the artist. The wording on the portrait includes the phrase, "With such humble work, Mr. Johann Engelbrecht deserves thanks." The identity of Johann Engelbrecht mentioned in this inscription has not been confirmed.

His son-in-law, Philipp Andreas Kilian, provided a detailed physical description of Martin Engelbrecht shortly before Engelbrecht's death. This description was recorded on the occasion of Engelbrecht's admission to the Inner Council of Augsburg in 1743 and was found in a manuscript written by Kilian. In this document, Kilian describes Engelbrecht as having a "high and broadly formed forehead," which revealed "great energy, skill, and tireless work." Kilian noted the "clarity and dignity" emanating from Engelbrecht’s "bright, lively eyes" and described his "strong nose" and "upright posture," which reflected his sense of well-being and status. Engelbrecht's appearance also included a "double chin" and a noticeable "sense of state pride," evident in his bearing. His well-tailored coat, marked with wide seams of soft cloth, added to his distinguished appearance, while his "strong, beautiful hand" held a few papers, signifying his role as an artist and businessman.

Legacy and Leadership - and Transition of Ownership:

In 1743, Engelbrecht was appointed to the Augsburg city council. His position not only added to his prestige but also likely gave him influence over local artistic policies, making his workshop a central part of Augsburg’s artistic landscape. He continued his work until his death on January 17, 1756. Following Engelbrecht's death, his business remained prosperous under the leadership of his daughters and sons-in-law. The enterprise continued its operations successfully, extending well into the 19th century.

After Martin Engelbrecht's death in 1756, some of his original engraved copperplates were sold to the Venetian publisher Remondini. This transfer likely occurred when the plates were no longer deemed valuable for reprinting. The Remondini family, based in Bassano del Grappa, was renowned for their extensive printing and publishing operations during the 18th century. They acquired numerous copperplates from various sources, including those of Engelbrecht, to expand their collection and reissue prints. This practice was common among publishers of the time, aiming to capitalize on existing artworks by producing new editions for the market.

Martin Engelbrecht had arranged for his youngest son to apprentice with three renowned copper engravers: Philipp Andreas Kilian, Christoph Friedrich Hörmann von und zu Gutenberg, and his son-in-law Christian Art Wilhelm (the husband of his daughter, Sibylla Engelbrecht). Upon Martin Engelbrecht's death, his estate, including the large publishing house and the property at C 90, was divided equally among his four heirs: his daughters Sibylla Wilhelm (married to Christian Wilhelm) and Hörmann (married to Christoph Hörmann), the widow of Philipp Andreas Kilian, and Georg Martin Kilian (son of Philipp Andreas Kilian).

In July 1756, shortly after Martin Engelbrecht’s death, Christoph Hörmann gained full control of the publishing house by purchasing the shares of the other heirs and mortgaging the C 90 property to complete the transaction. However, by 1758, Christian Wilhelm had become the sole owner of the Martin Engelbrecht publishing house. The specifics of how Christian Wilhelm took over from Hörmann remain unclear, but it was likely through a family arrangement or the sale of Hörmann's shares. Christian Wilhelm’s closer ties to the family and possibly greater ability to manage the business may have influenced this transition.

Christian Wilhelm continued to operate the publishing house under the Martin Engelbrecht name, though there is little documentation about his activities as an artist or publisher. He lived to the age of 81 and was known for his controversial membership in the Imperial Franciscan Academy of Fine Arts and Sciences, a move likely aimed at protecting the business from competition. Despite the controversies surrounding the academy, Wilhelm managed the publishing house until his death.

Decline and Closure:

In 1787, the publishing business passed to Paul Martin Wilhelm, the son of Christian Wilhelm. Paul was one of Christian's 14 children. Paul took over the publishing house in January 1787 at the age of 30 and managed it until 1822. By that time, the company primarily focused on producing copper engravings, though it is assumed that the family continued some production of artistic prints.

During Paul Martin Wilhelm’s tenure, the imperial privilege originally granted to Martin Engelbrecht in 1719, and renewed in 1739, had expired, likely due to the high costs associated with maintaining it. As a result, unauthorized reproductions of Engelbrecht’s popular engravings by unscrupulous imitators became widespread in the late 18th century. To combat this, Paul Martin Wilhelm took decisive action. On November 30, 1787, he addressed the High Council, submitting samples of his works and humbly requesting their favor in granting him a new privilege to prevent the counterfeiting of his bronzed copper engravings. This request, laced with a hint of grim humor, reflected the struggles faced by printmakers like Paul Martin Wilhelm, whose high-quality works were frequently targeted by plagiarists.

In 1822, Paul Martin Wilhelm handed over the entire publishing business to his son, Christian, as part of Christian’s impending marriage. In a statement, Paul Martin declared, "In truth, I declare that I have handed over the entire business to my son Christian, upon his impending marriage, to be managed and owned by him alone, and that there is a maternal fortune of 2000 florins." Despite stepping down, Paul Martin continued to live independently into his old age.

Christian’s son, Jakob Christian Martin Wilhelm, managed the Engelbrecht family publishing business from 1822 until his tragic death on January 22, 1826, after suffering a stroke. Ownership of the business passed to his heirs, and his widow managed the operations until the end of 1827. However, on January 1, 1828, Johann Aloys Schlosser acquired the Martin Engelbrecht Book and Art Shop, rebranding it as "J. A. Schlosser's Buch- und Kunsthandlung" (J. A. Schlosser's Book and Art Shop). This acquisition marked the end of the Engelbrecht-Wilhelm era and brought the long history of the Martin Engelbrecht company to a close after more than a century of success.

In the 1860s, J. A. Schlosser's Book and Art Shop reduced its focus on publishing art and shifted almost entirely to bookselling.

Engelbrecht’s Lasting Impact

Engelbrecht’s influence extended far beyond the 18th century, positioning him as a key figure in the evolution of optical entertainment technologies. His innovative use of layered engravings and perspective to create three-dimensional illusions marked him as a pioneer in the development of visual storytelling techniques that would later become central to the fields of photography and cinema.

While Engelbrecht's perspective theaters were rooted in the Baroque era's love of spectacle and innovation, they laid the foundation for the later development of paper peepshows in the 19th century. Paper peepshows of Victorian England expanded on Engelbrecht's concept, adapting it for a growing middle-class audience interested in travel, popular entertainment, and cultural landmarks. This new wave of peepshows depicted contemporary attractions like the Crystal Palace, leveraging similar layered techniques to create engaging visual experiences. The appeal of paper peepshows was deeply tied to the visual culture of their time. They drew inspiration from other popular forms of entertainment, such as panoramas, theatrical performances, and magic lantern shows, all of which shaped the Victorian fascination with immersive experiences.

The optical effects achieved through Engelbrecht’s dioramas and miniature theaters prefigured many of the principles that would define later advancements in visual media. His use of depth, perspective, and the manipulation of light and shadow laid the groundwork for the camera obscura and early experiments with photography in the 19th century. By employing techniques that made flat images appear three-dimensional, Engelbrecht was, in essence, creating a proto-cinematic experience, inviting viewers to become immersed in the visual narratives he crafted.

Engelbrecht’s influence can also be seen in the development of early motion pictures. The layered scenes and staged sequences in his dioramas mimic the way films would later use sets, framing, and perspective to guide the viewer's eye through a story. His mastery of visual storytelling through static images had a direct impact on how later generations of artists, photographers, and filmmakers approached the representation of movement and depth on screen. The theatrical quality of his works, with their vivid compositions and lifelike scenes, foreshadowed the use of special effects in modern cinema, where optical illusions are used to engage and entertain audiences.

In this sense, Engelbrecht’s work is not just a reflection of Baroque-era fascination with illusion and spectacle but also a precursor to the visual technologies that shape our world today. His dioramas and optical theaters stand as early examples of interactive entertainment, where viewers are invited to engage with the artwork in a way that mirrors how modern audiences interact with films, virtual reality, and other forms of immersive media.

Through his technical innovation and artistic vision, Engelbrecht’s legacy lives on in the fields of photography, cinema, and modern visual storytelling, marking him as an essential figure in the history of optical art.

References:

Schott, Friedrich (1867-1928).Der Augsburger Kupferstecher und Kunstverleger Martin Engelbrecht und seine Nachfolger: ein Beitrag zur Geschichte des Augsburger Kunst- und Buchhandels von 1719 bis 1896. Augsburg: Schlosser, 1924.

(Friedrich Schott's 1924 catalog remains a vital resource for researchers and art historians studying Engelbrecht's extensive oeuvre. It provides detailed insights into the artist's contributions to engraving and art publishing in Augsburg during the 18th century.)

Deutsche Biographie. "Engelbrecht, Martin." Neue Deutsche Biographie, vol. 4, 1959, p. 512. Accessed November 20, 2024. https://www.deutsche-biographie.de/pnd118684728.ht...

Crepin, Daniel. Tagungsband Ravenna 2006: Les théâtres pour boîtes d'optique au XVIIIe siècle. Le Vieux Papier, no. 309. Société Le Vieux Papier, 2006, pp. 155-158.

Milano, Alberto. Martin Engelbrecht: Perspektivtheater - Dioramen. Füsslin Verlag, 2016.

Planting Diaries. "Martin Engelbrecht." Planting Diaries. https://plantingdiaries.com/category/martin-engelb... Accessed September 4, 2024.

Wikipedia contributors. "Martin Engelbrecht." Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. https://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Martin_Engelbrecht.

University of Edinburgh. Peepshow depicting a library by Martin Engelbrecht. University of Edinburgh Archive. Accessed September 4, 2024.

Robinson, David. “Review: Augsburg Peepshows.” Print Quarterly, vol. 5, no. 2 (June 1988), pp. 188-91.

Hyde, Ralph, and Erkki Huhtamo. Paper Peepshows: The Jacqueline and Jonathan Gestetner Collection. Woodbridge: Antique Collectors' Club, 2015.

Feingold, Mordechai, and Martin Stuber, eds. Scholars in Action: The Practice of Knowledge and the Figure of the Savant in the 18th Century, vol. 2. Leiden: Brill, 2013.

Milano, Alberto. "The Theatrical Dioramas of Martin Engelbrecht." Barockberichte, no. 40/41, 2005, pp. 704–711.

Wikipedia contributors. "Gottlieb Tobias Wilhelm." Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia.

(14 children for Christian.) Graphic Sources for Meissen Porcelain: Origins of the Print Collection in the Meissen Archives.

(In this article, the Remondini family's involvement is discussed in footnote 34. This footnote references Mario Infelise and Paola Marini's work, Remondini / Un Editore del Settecento (Milan, 1990), specifically page 227, note 13.)

Shijia Yu's doctoral thesis, titled "Amusing, Interesting, and Curious: The Paper Peepshow in England, 1825-1851